Lifespan Extension at Low Temperatures is Genetically Controlled, Study Suggests

WOODS HOLE, Mass. —Why do we age? Despite more than a century of research (and a vast industry of youth-promising products), what causes our cells and organs to deteriorate with age is still unknown.

One known factor is temperature: Many animal species live longer at lower temperature than they do at higher temperatures. As a result, “there are people out there who believe, strongly, that if you take a cold shower every day it will extend your lifespan,” says Kristin Gribble, a scientist at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL).

But a new study from the laboratories of Gribble and MBL Director of Research David Mark Welch indicates that it’s not just a matter of turning down the thermostat. Rather, the extent to which temperature affects lifespan depends on an individual’s genes.

The MBL study, published in Experimental Gerentology, was conducted in the rotifer, a tiny animal that Gribble, Mark Welch, and colleagues have been developing as a modern model system for aging research. They exposed 11 genetically distinct strains of Brachionus rotifers to low temperature, with the hypothesis that if the mechanism of lifespan extension is purely a thermodynamic response, all strains should have a similar lifespan increase.

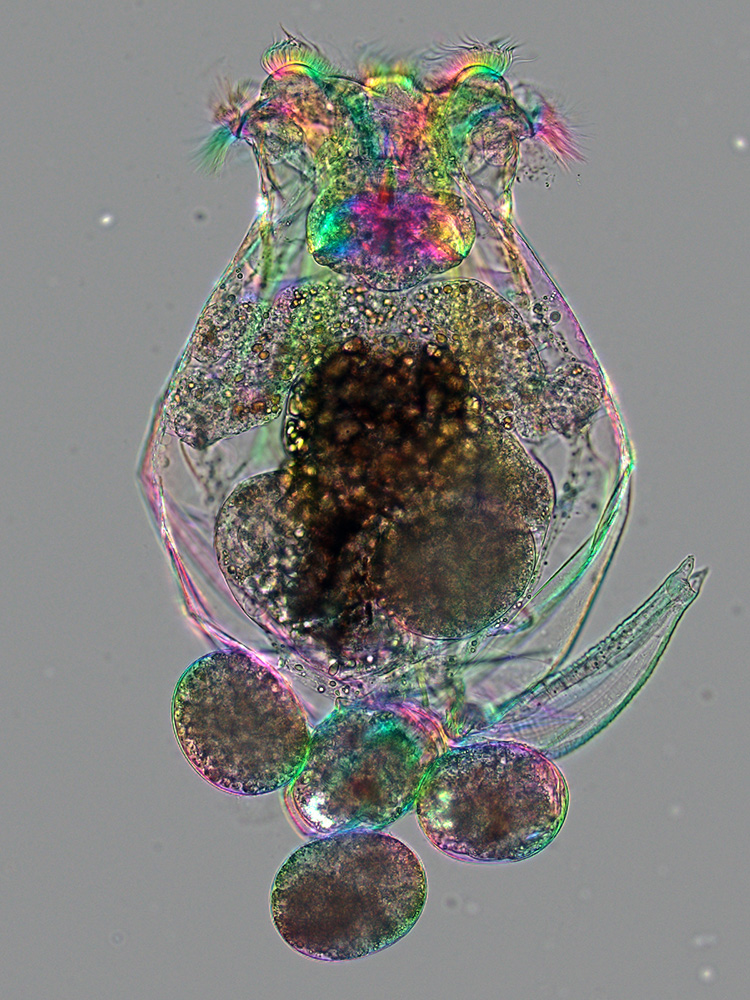

A female rotifer (Brachionus), a model system for aging studies. Credit: Michael Shribak and Kristin Gribble

A female rotifer (Brachionus), a model system for aging studies. Credit: Michael Shribak and Kristin GribbleHowever, the median lifespan increase ranged from 6 percent to 100 percent across the strains, they found. They also observed differences in mortality rate.

The study clarifies the role of temperature in the free-radical theory of aging, which has dominated the field since the 1950s. This theory proposes that animals age due to the accumulation of cellular damage from reactive oxidative species (ROS), a form of oxygen that is generated by normal metabolic processes.

“Generally, it was thought that if an organism is exposed to lower temperature, it passively lowers their metabolic rate and that slows the release of ROS, which slows down cellular damage. That, in turn, delays aging and extends lifespan,” Gribble says.

Their results, however, indicate that the change in lifespan under low temperature is likely actively controlled by specific genes. “This means we really need to pay more attention to genetic variability in thinking about responses to aging therapies,” Gribble says. “That is going to be really important when we try to move some of these therapies into humans.”

Citation:

Gribble, Kristin E et al (2018) Congeneric variability in lifespan extension and onset of senescence suggest active regulation of aging in response to low temperature. Experimental Gerentology 114: 99-106, doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.10.023

More Information

Rotifers are small, aquatic animals with about 1,000 cells, a brain and nervous system, and muscle, digestive and reproductive systems. They offer many advantages as a model organism for biomedical research, including aging studies:

- Rotifers have more genes in common with humans than do other popular invertebrate models (fruit flies and nematodes).

- Short lifespan (about two weeks), allowing for rapid lifespan assays.

- Easy to culture in laboratory.

- Rotifers are transparent, allowing for imaging of cellular processes.

- A great deal is known about rotifer ecology: how they reproduce and thrive in the natural world.

- A draft genome is sequenced and transcriptome is published.

Background:

Mark Welch, David. The Potential of Comparative Biology to Reveal Mechanism of Aging in Rotifers. In Conn’s Handbook of Models for Human Aging (Elsevier, 2018) doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-811353-0.00037-3

Gribble, Kristin E and David B. Mark Welch (2017) Genome-wide transcriptomics of aging in the rotifer Brachionus manjavacas, an emerging model system. BMC Genomics, doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3540-x.

—###—

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is dedicated to scientific discovery – exploring fundamental biology, understanding marine biodiversity and the environment, and informing the human condition through research and education. Founded in Woods Hole, Massachusetts in 1888, the MBL is a private, nonprofit institution and an affiliate of the University of Chicago.