Logan Science Journalism Fellows Experience Life in the Lab

What happens when you put professional journalists, writers and editors in a research laboratory for 10 days with scientific faculty? They learn how to micropipette, quantify water samples, analyze the genomes of sea urchins — and make scientific discoveries along the way.

“For those 10 days we briefly became scientists,” says Mićo Tatalović, a science journalist from Croatia and a 2018 Logan Science Journalism Fellow. “I was so impressed by how much we achieved, going from field work to lab analyses and then to data interpretation and presentations, all in just a matter of days.”

The Logan Science Journalism Program competitively selects professionals from around the world to receive hands-on training in contemporary scientific research techniques. Each fellow joins either the Biomedical or the Environmental Hands-On Research Course. The fellows form their own research questions and, with the help of scientific faculty, engage in experiments and field work to answer them.

This year, the Environmental Fellows studied estuaries where freshwater and saltwater mix, to measure how severely human activity is altering these natural areas. After sampling groundwater from several estuaries near Woods Hole, the fellows found higher nitrogen levels and more algae at sites near sizable human populations and urban development than in less-populated areas. They measured the amount of algae and its rate of oxygen consumption in each habitat to confirm that in excess, nitrogen causes an overgrowth of algal species that use up the oxygen in an ecosystem — killing off habitat, such as eelgrass, and disrupting the coastal food chain. The fellows also learned how to use stable isotope analysis to show that wastewater influx could be a contributing factor to excess nitrogen and algal growth.

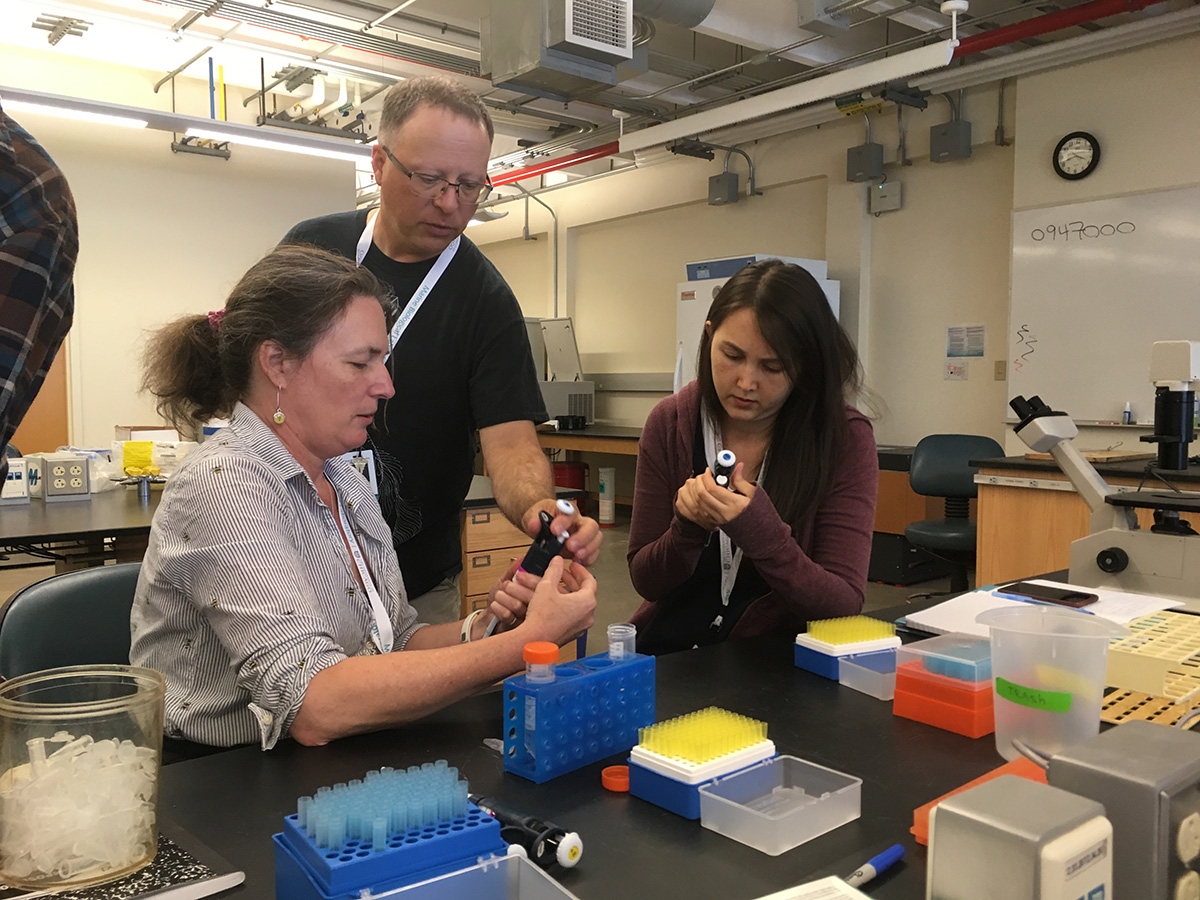

The Biomedical Fellows worked with two well-established model organisms in biomedical research: yeast cells, which are widely used as genetic model organisms, and sea urchins, which are particularly useful for studying fertilization and early development. They screened an array of yeast mutants with genetic changes or deletions that affect mitochondria, cell division and cell shape. They were able to identify several genes with major effects on cells’ shape and energy production, including one that fully wiped out the mitochondria’s ability to produce energy.

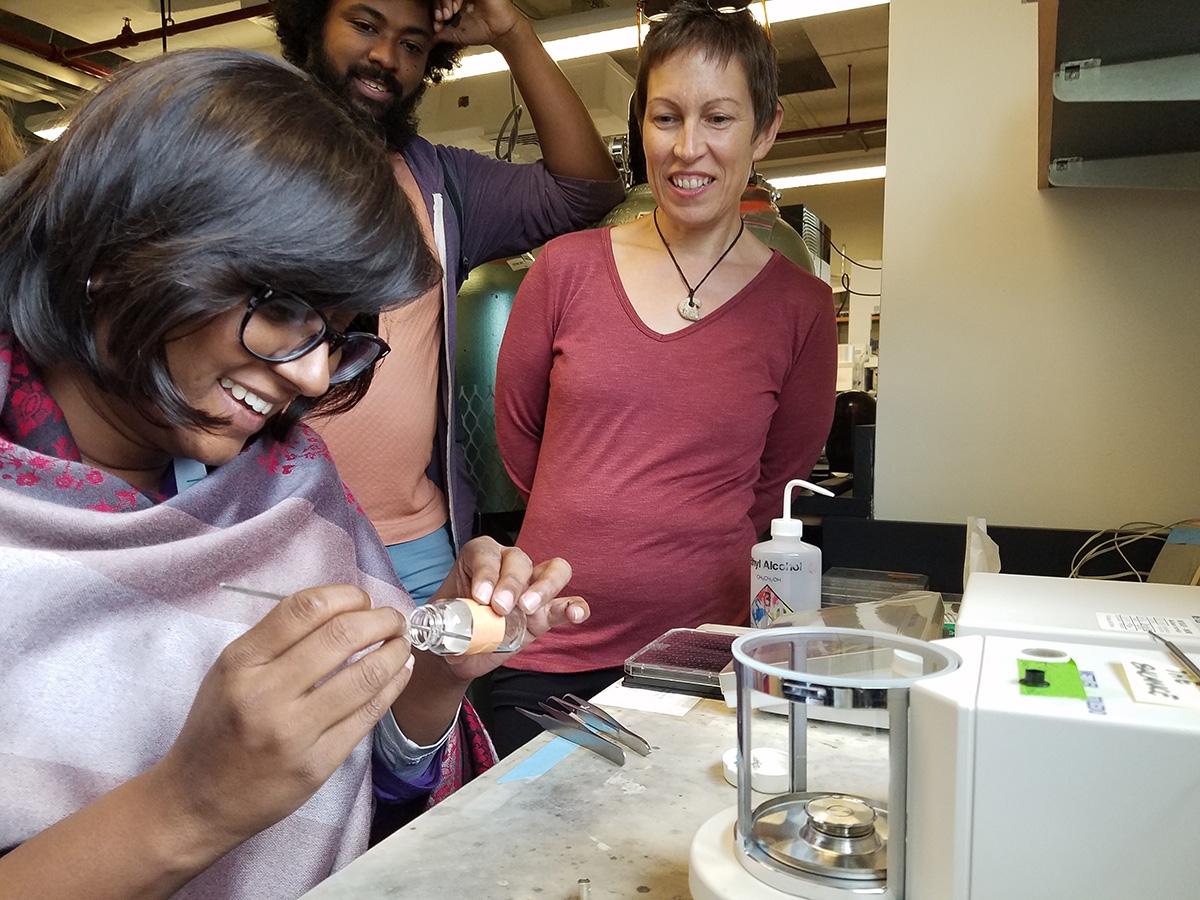

The Biomedical Fellows also observed a specific population of cells within a sea urchin embryo. These cells use tiny, finger-like projections, called filopodia, to sense their surroundings and travel inside the embryo, later forming the animal’s skeleton. The fellows cultured these cells to explore how the environment outside the cell affects filopodia formation. When they blocked the function of proteins that help build the filopodia, the cells struggled to navigate within the embryo, slowing or halting embryonic development.

After hours of work in the lab and the field, pipetting minuscule amounts of genetic material and collecting samples of bacteria and algae from the water, the fellows emerged more confident in their ability to not only interpret scientific findings, but to explain these findings to a broader audience, strengthening their skills as science journalists.

“I gained a better understanding of the scientific process,” says Lorelei Goff, a freelance journalist from Greeneville, Tennessee, and a 2018 fellow in the program. “For me, this translates into more reliable reporting, better working relationships with scientists as sources, and can help build the public's trust in science and science reporting.”