Mechanisms of Wound Healing are Clarified in Zebrafish Study

WOODS HOLE, Mass.— A crucial component of wound healing in many animals, including humans, is the migration of nearby skin cells toward the center of the wound. These cells fill the wound in and help prevent infection while new skin cells regenerate.

How do these neighboring skin cells know which way to migrate? What directional cues are they receiving from the wound site? A new paper by Mark Messerli and David Graham of the MBL’s Eugene Bell Center for Regenerative Biology and Tissue Engineering clarifies the role of calcium signaling in this medically significant communication between skin cells.

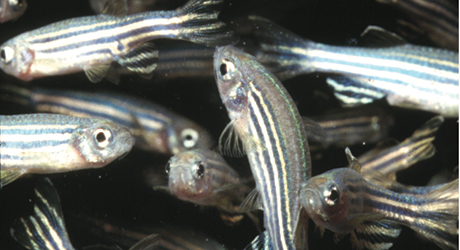

Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Credit: Lukas Roth

Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Credit: Lukas RothMesserli and Graham conducted the study using zebrafish skin cells, which migrate much faster than human cells. “Fish have to heal quickly,” Messerli says. “They are surrounded by microbes and fungi in the water. They are constantly losing scales, which generates a wound. So the wound has to be healed in the epidermis first and then a new scale has to be built. Fish skin cells (keratinocytes) migrate five times faster at room temperature than mammalian cells do at 37 degrees C. So it is very easy to track and follow their migratory paths in a short period of time.“

The study brought fresh insights on the role of calcium signaling in inducing cellular organization and directed migration of skin cells. “When we started this study, we were looking at calcium signaling at the single-cell level, which is how it has been looked at for decades. How do single cells see injury?” Messerli says.

To their surprise, by the end of the study they were looking at the calcium signals not just in single cells but in sheets of cells that surround wounds. “The periphery of the wound itself appears to form a graded calcium signal that could direct migration and growth toward the center of the wound. This is what we are looking at now,” Messerli says.

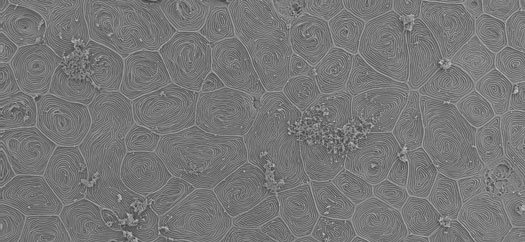

Skin of the adult zebrafish. The distinctive labyrinth-like patterns seen on most of the cells are actin micro-ridges that are characteristic of superficial skin cells. Another version of this SEM image appears on the cover of the Oct. 15 issue of Journal of Cell Science with Graham and Messerli's study. Credit: David Graham

Skin of the adult zebrafish. The distinctive labyrinth-like patterns seen on most of the cells are actin micro-ridges that are characteristic of superficial skin cells. Another version of this SEM image appears on the cover of the Oct. 15 issue of Journal of Cell Science with Graham and Messerli's study. Credit: David GrahamThe team’s approach was to use advanced microscopy to monitor cellular calcium signals and molecular analysis to identify membrane proteins that caused increases in cellular calcium migration. A variety of mechanically activated ion channels were identified in migratory skin cells. TRPV1, the ion channel that is also activated by hot peppers, was found to be necessary for migration.

Messerli’s co-authors on the paper include David Graham, formerly a research assistant at MBL and now a graduate student at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill School of Medicine, and colleagues at Purdue University. Messerli also holds an appointment in the MBL’s Cellular Dynamics Program.

Citation:

Graham DM, Huang L, Robinson KR, and Messerli MA (2013) Epidermal keratinocyte polarity and motility require Ca2+ influx through TRPV1. J Cell Sci. 126: 4602-4613.

—###—

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is dedicated to scientific discovery and improving the human condition through research and education in biology, biomedicine, and environmental science. Founded in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, in 1888, the MBL is a private, nonprofit institution and an affiliate of the University of Chicago.