Microscope Invented at MBL Reveals Density of Chromosomal “Dark Matter”

Using a microscope invented at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), a collaborative team of biologists, instrument developers, and computational scientists has for the first time measured the density of a relatively inscrutable, highly condensed form of chromosomal material that appears in the cells of human beings and other eukaryotes. MBL scientists Michael Shribak (the microscope’s inventor) and Tomomi Tani, together with Kazuhiro Maeshima of the National Institute of Genetics, Japan, recently reported their findings in Molecular Biology of the Cell.

The scientists measured the density of heterochromatin, a tightly packed form of chromatin that appears as dark, scattered regions in the cell nucleus. Until recently, this chromosomal “dark matter” was thought to contain either noncoding DNA or silenced genes; however, new research suggests that heterochromatin DNA is not, in fact, fully inactive. To investigate this possibility, the physical properties of heterochromatin need to be described in live cells, which has been a significant challenge using traditional microscopy. The team was able to measure the density of heterochromatin in its natural state using a novel type of microscopy, orientation-independent differential interference contrast (OI-DIC), which Shribak first developed in collaboration with MBL Distinguished Scientist Shinya Inoué in the mid-2000s and has continued to improve.

This study, Shribak said, is “the first important application of OI-DIC,” a technology that “is ideal for studying structure and motion in unstained, living cells and isolated organelles, because they can be followed for long periods of time non-invasively.”

“This research exemplifies the kind of successful and productive interaction between biologists, microscope developers, and data scientists that is a central feature of MBL science, and is a major area of growth at the MBL,” said David Mark Welch, director of the Marine Biological Laboratory Division of Research.

Widely used by biologists since the 1970s, conventional DIC microscopy uses beam-shearing interference to generate contrast-based images of live, unmodified cells and tissues. In the early 1980s at MBL, Shinya Inoué and Robert and Nina Allen of Dartmouth College independently invented video-enhanced DIC, which drastically improved the technique and its resolution. However, DIC suffered still from the drawback that the scientist had to rotate the biological sample several times to get a complete image, because cellular structures along the beam-shearing plane are invisible. In 2002, Shribak proposed orientation-independent DIC (U.S. patents 7233434 and 7564618), which solved the problem. The OI-DIC microscope rapidly takes images in different beam-shear directions, then processes a final image. It has the added advantage over conventional DIC of allowing quantitative measurement of the sample.

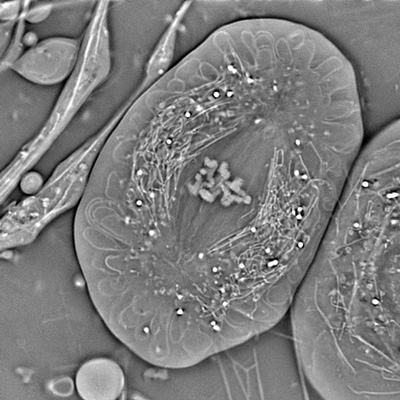

Crane fly spermatocyte (full metaphase of meiosis I) imaged with OI-DIC. Credit: Michael Shribak and James LaFontain (SUNY at Buffalo)

Crane fly spermatocyte (full metaphase of meiosis I) imaged with OI-DIC. Credit: Michael Shribak and James LaFontain (SUNY at Buffalo)Last summer, Thomas Rhines, a University of Chicago student studying with Shribak as a Jeff Metcalf Undergraduate Scholar, developed a method to measure the resolution of optical microscopes, focusing particularly on the OI-DIC. “This microscope provides the best possible resolution and contrast [of DIC microscopes],” Shribak said (about 250 nm at highest resolution). Rhines and Shribak will continue to collaborate to develop the best algorithm for data analysis of resolution. Shribak is also collaborating with MBL Fellow Patrick La Rivière of the University of Chicago to develop a 3D orientation-independent DIC system.

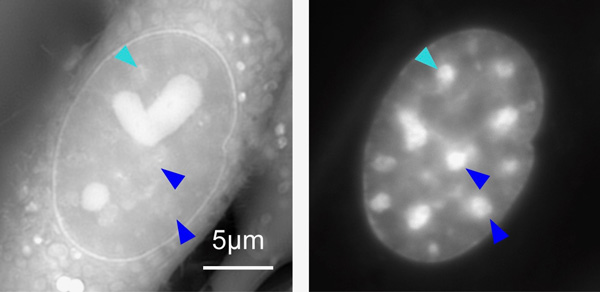

At left: OI-DIC image of a live mouse cell visualizing density of materials. The bright regions with the heart- and sphere-shapes are compartments in the cell called nucleoli. At right: A conventional fluorescence microscopy image of the same cell depicting only DNA. The bright regions are the heterochromatin. Some heterochromatin are marked with arrow heads for comparison between the two images. Note that they look different because the fluorescence image (right) does not necessarily show density of the materials. From Imai et al (2017) DOI: 10.1091/mbc.E17-06-0359

At left: OI-DIC image of a live mouse cell visualizing density of materials. The bright regions with the heart- and sphere-shapes are compartments in the cell called nucleoli. At right: A conventional fluorescence microscopy image of the same cell depicting only DNA. The bright regions are the heterochromatin. Some heterochromatin are marked with arrow heads for comparison between the two images. Note that they look different because the fluorescence image (right) does not necessarily show density of the materials. From Imai et al (2017) DOI: 10.1091/mbc.E17-06-0359Citation:

Imai, Ryosuke et al. Density imaging of heterochromatin in live cells using orientation-independent-DIC microscopy. Mol. Biol. Cell, published online before print August 23, 2017. DOI: 10.1091/mbc.E17-06-0359

—###—

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is dedicated to scientific discovery – exploring fundamental biology, understanding marine biodiversity and the environment, and informing the human condition through research and education. Founded in Woods Hole, Massachusetts in 1888, the MBL is a private, nonprofit institution and an affiliate of the University of Chicago.